Built Heritage Tradition of the Sta. Ana Church

Built Heritage Tradition of the Sta. Ana Church

(Parish Church of Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados) in Sta. Ana, Manila City

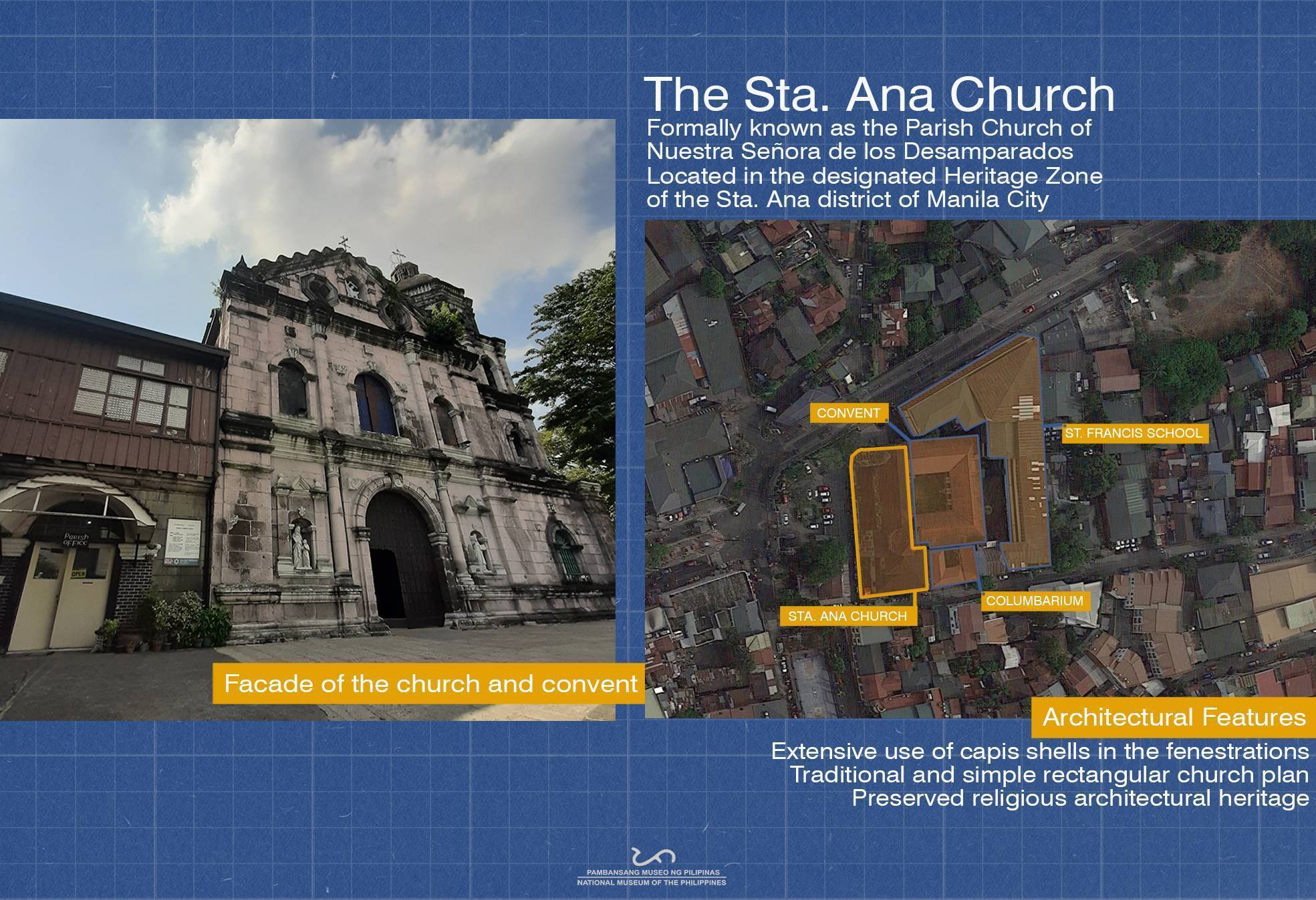

In our #MuseumFromHome series, this week’s feature of our #BuiltTraditionThursday is the Sta. Ana Church, formally known as the Our Lady of the Abandoned Parish. Located in a declared and protected Heritage Zone in the district of Sta. Ana in Manila City, the parish church tracing its origins to the 1500s is also notable for being site and setting of two declared National Cultural Treasures of the country, the Camarin dela Virgen and the Sta. Ana Site Museum. The Parish Church is a significant example of enduring architectural and cultural Filipino heritage.

The Sta. Ana Church is a Spanish colonial period church. Its site was established by the Spanish Franciscan Missionaries in 1578, in the first settlement established outside of Intramuros. Originally of nipa and bamboo make, construction of a larger church in stone begun around 1720 and finished in 1725 upon the direction of then parish priest, Fr. Vicente Ingles. In time, the church became known as Our Lady of the Abandoned Parish, as it also houses the centuries old and miraculous image of Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados, which was brought by Fr. Ingles from Spain.

Over the centuries, Sta. Ana church has suffered the inclemency of tropical weather and has survived major earthquakes. Fortunately, it was saved from World War II, while the rest of Manila burned down, the town and the church stood unscathed. In 1977, major restoration was undertaken by the National Artist Juan F. Nakpil with the assistance of Engineer Arturo Mañalac to bring out the church’s original appearance for the town of Sta. Ana’s 400th anniversary.

Over the centuries, Sta. Ana church has suffered the inclemency of tropical weather and has survived major earthquakes. Fortunately, it was saved from World War II, while the rest of Manila burned down, the town and the church stood unscathed. In 1977, major restoration was undertaken by the National Artist Juan F. Nakpil with the assistance of Engineer Arturo Mañalac to bring out the church’s original appearance for the town of Sta. Ana’s 400th anniversary.

The current state of the Sta. Ana Church itself depicts Baroque style structure, with elements suggesting a composite of the characteristic features of religious architecture. The main church features a long hall nave with no transepts. The structure measures an estimated sixty-three (63) meters by thirty (30) meters and is oriented with the longitude along the North and South axis, with the main entrance on the North façade and the convent and cloisters along the East side of the main church structure. The construction of the main church utilized stone and stucco finish with Philippine hardwood.

The Sta. Ana Church is also notable for its extensive use of capis in its windows and fenestrations. These extant capis are found throughout the church, but are most prevalent in the convent courtyard; featuring a gallery corridor measuring approximately four (4) meters in width, with the exception of the Western corridor which is attached to the church proper and measuring six (6) meters in width. This gallery corridor wraps around the entirety of the convent courtyard, overlooking the central patio, and is comprised entirely of sliding windows that feature capis shells, with panes of the shell in first and second grade, ranging in size from a 5 to 7 centimeter square.

The Sta. Ana Church is also notable for its extensive use of capis in its windows and fenestrations. These extant capis are found throughout the church, but are most prevalent in the convent courtyard; featuring a gallery corridor measuring approximately four (4) meters in width, with the exception of the Western corridor which is attached to the church proper and measuring six (6) meters in width. This gallery corridor wraps around the entirety of the convent courtyard, overlooking the central patio, and is comprised entirely of sliding windows that feature capis shells, with panes of the shell in first and second grade, ranging in size from a 5 to 7 centimeter square.

Each wall of the square inner structure facing out unto the patio includes four (4) unit sets of windows, with each unit comprising of eight (8) panels: this totals to thirty-two (32) panels per wall, and one hundred and twenty-eight (128) sliding panels in the convent. Each individual sliding window panel contains approximately (100) individual capis panes, distributed into two sections of the panel, considering the aforementioned total of one hundred and twenty-eight (128) panels in the convent this totals to approximately twelve-thousand and eight hundred (12,800) capis panes within the sliding windows of the convent alone.

Each wall of the square inner structure facing out unto the patio includes four (4) unit sets of windows, with each unit comprising of eight (8) panels: this totals to thirty-two (32) panels per wall, and one hundred and twenty-eight (128) sliding panels in the convent. Each individual sliding window panel contains approximately (100) individual capis panes, distributed into two sections of the panel, considering the aforementioned total of one hundred and twenty-eight (128) panels in the convent this totals to approximately twelve-thousand and eight hundred (12,800) capis panes within the sliding windows of the convent alone.

Currently, the Sta. Ana Church is amongst Manila’s built heritage structures featured at the National Museum of Philippines’ interdisciplinary exhibition, “Placuna placenta: Capis Shells and Windows to Indigenous Artistry” waiting for visitor’s appreciation, a panel of the capis windows from the church convent is also currently loaned from the parish to the exhibit. The Sta. Ana Church is representative of the country’s religious history, and its significance is manifested clearly in its preservation and long-enduring place in the community it represents.

Currently, the Sta. Ana Church is amongst Manila’s built heritage structures featured at the National Museum of Philippines’ interdisciplinary exhibition, “Placuna placenta: Capis Shells and Windows to Indigenous Artistry” waiting for visitor’s appreciation, a panel of the capis windows from the church convent is also currently loaned from the parish to the exhibit. The Sta. Ana Church is representative of the country’s religious history, and its significance is manifested clearly in its preservation and long-enduring place in the community it represents.

You can appreciate this architectural marvel at the Gallery 20, third level of the National Museum of Fine Arts or see the virtual exhibition thru this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTpyLDCaero

You can appreciate this architectural marvel at the Gallery 20, third level of the National Museum of Fine Arts or see the virtual exhibition thru this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BTpyLDCaero

Text and illustrations/photos by Ar. Armando Arciaga III of the NMP Architectural Arts And Built Heritage Division