Undas 2021 (Lapida)

Undas (Lapida)

-

November 1 – Undas (Lapida) A

-

November 1 – Undas (Lapida) B

-

November 1 – Undas (Lapida) C

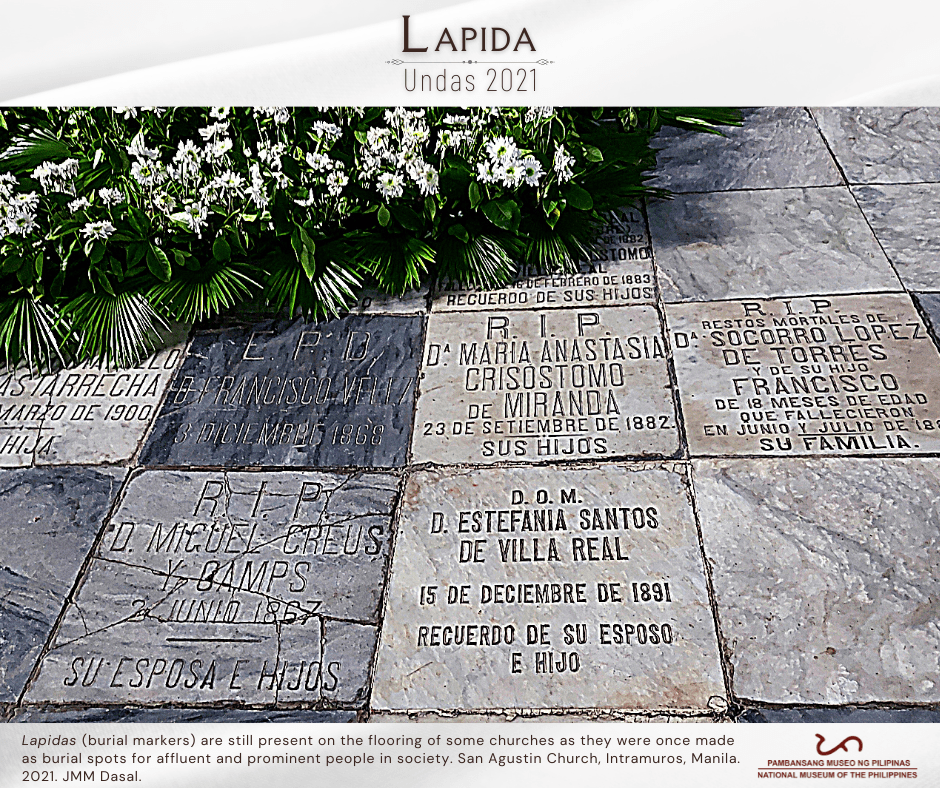

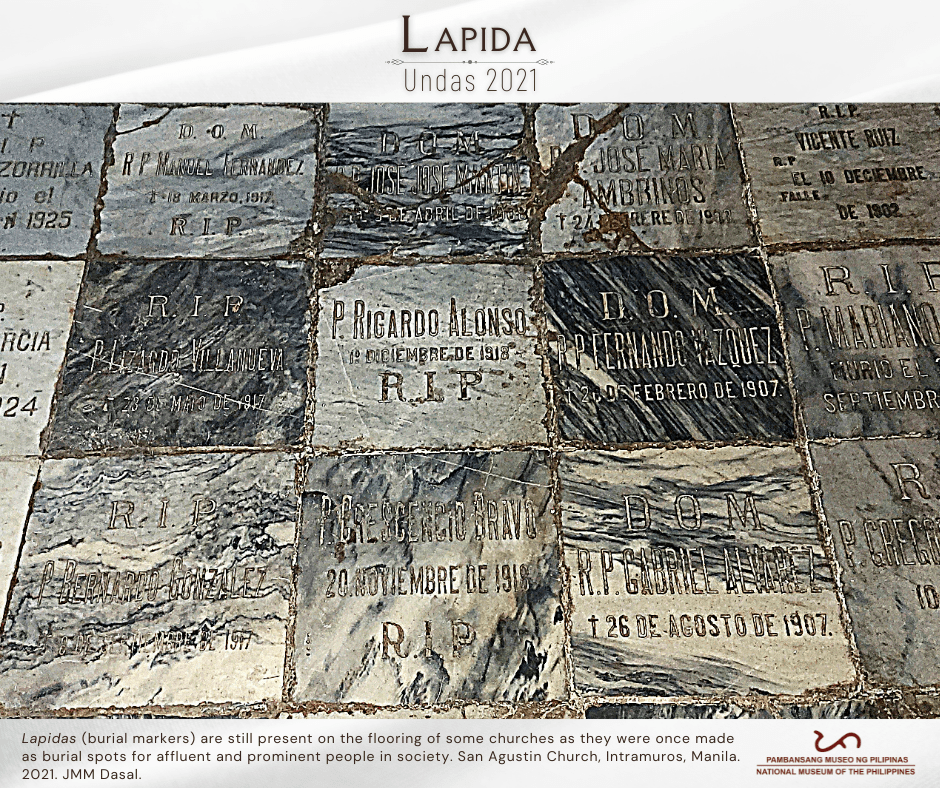

In the observance of #Undas2021 with our Filipino brothers and sisters today, All Saint’s Day, our #MuseumFromHome series features an important burial element —the lapida.

Undas generally refers to the observance of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day every 1st and 2nd day of November, respectively. Filipino Christians gather with their families in cemeteries to pray and pay tribute to their departed loved ones. Family members clean the nitso (grave) a few days before the observance. They prepare the cleaning materials and equipment and locate the grave of their loved ones, which could be a challenging task in public cemeteries due to overcrowding. That is why burial markers, known as lapida or headstones/ tombstones, are of great importance in finding the grave of the dead family members.

Lapida are commonly made of marble slab bearing information about the deceased—the complete name, and dates of birth and death—engraved on its surface, serving as a permanent marker on the grave of the dead. Some markers include the title of the deceased, or even figures indicating the time of death, a prayer, epitaph, among others. Aside from marble, the lapida can also be made from cement, ceramic tile, or granite.

Burial spaces inside old churches is common in the Philippines, as internment inside and/or in crypts were practices during the early times, one reason is due to the belief that souls of the departed must be blessed with constant prayers—a church is the perfect place. People who were interred inside old churches were often bishops, high-ranking government officials, and prominent figures of the community—mostly members of wealthy families. The altar and floor serve as burial grounds and, in some instances, lapida may also be found along church walls, a constant reminder of the influence of the interred individual. The said practice is a way of honoring the person, making their legacy known to the younger generation and showing that they had the privilege to have a place of worship as a final destination.

As we remember our dearly departed this Undas season, #KeepSafe and be mindful in following the IATF rules related to this event as well as safety and health protocols. Check on the works of Dr. Grace Barretto-Tesoro on grave markers in the country for an in-depth look into the topic.

#Undas2021

#Lapida

#GraveMarkers

#PhilippineCultureAndTradition

Text and poster by the NMP Ethnology Division

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)