Apuh Ambalang and the Yakan Weaving Tradition

Apuh Ambalang and the Yakan Weaving Tradition

-

DSCF4763

-

DSCF4767

-

DSCF4769

-

DSCF4770

Weaving is an extremely important craft in the Yakan community. All Yakan women in the past were trained in weaving. Long ago, a common practice among the Yakan was that, when a female was born, the pandey, traditional midwife, would cut the umbilical cord using a wooden bar called bayre (other Yakan pronounce this as beyde). That bar was used for ‘beating-in’ the weft of the loom. By thus severing of the umbilical cord, it was believed that the infant would grow up to become an accomplished weaver. This, and all other aspects of the Yakan weaving tradition, is best personified by a seventy-three-year-old virtuoso from the weaving domicile of the Yakan in Parangbasak, Lamitan City: Ambalang Ausalin. (Pasilan, 2016a)

Ambalang Ausalin, a Manlilikha ng Bayan from Parangbasak, Lamitan City, was born on March 4, 1943. She is known among the weavers as “Apuh Ambalang.“ She is knowledgeable of the entire weaving process, from the meghani (warping), nuwah (filling-in the comb), meneh (creating the design), and nennun (the actual weaving). Aside from this, she could clearly define and express the cultural significance of each textile design or category. When she was a young girl, her mother, who was the best weaver during her time, tutored her. The young Ambalang would use strips of coconut leaves (used in mat-making) as practice material, and having taught by her mother – Apuh Bariya, she started to weave using the back strap loom. From the “bunga- sama teed peneh pitumpuh,” to trying the “sineluan” and then, the “seputangan.” These are three of most intricate textiles in Yakan weaving, as these would require the filling of miniscule details of geometric designs on the warp.

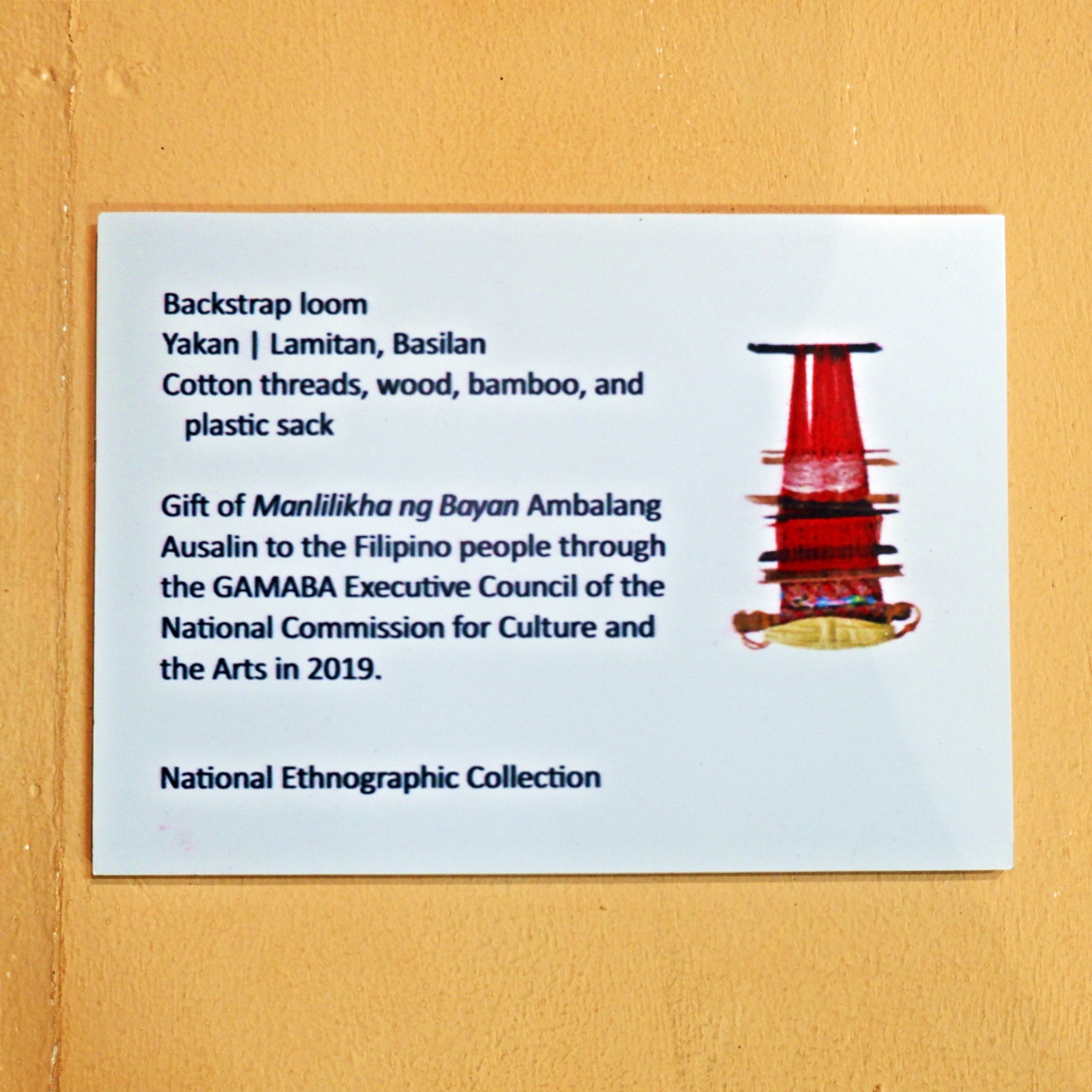

Yakan weavers, like Apuh Ambalang, would use the tennun or the body tension loom or the back strap tension loom where the weaver sits on the floor with the loom being controlled by her body. Yakan looms can be small or large depending on the type of cloth or design to be woven, and they can be rolled up, carried, and easily set up. The rolled-up warp can be held up in one of the beams at a traditional home. The weaver sits on the floor before the loom with a belt on her waist called awit also called ikus and a warp beam, deddug, suspended on a house beam, diagonally in front of her. She braces her feet against a piece of wood called tindakan, and uses her body to keep the warp threads taut and in place. The warp is wound eight to ten meters or longer, just enough to make it easy for setting up the loom inside the house in a process known among the weavers as peghani. The threads are pulled through a bamboo comb, sud, one at a time, in a procedure called nuwah, so that the threads will be evenly spaced. The secret of an intricately woven cloth lies in the comb, sud dendam: the more the number of sticks that make up the comb, the closer its teeth, therefore, the tighter and more embossed or lifted the designs will be. The pattern or design is made by counting the threads of the loom for each row. Each row is bundled with a separate piece of yarn or sack thread, tabid, so it can be used throughout the length of the loom. This process is called megpeneh (choosing the threads/making up the design). In this way the whole pattern is pre-programmed. This method is used in almost all cloth designs except for the seputangan (female head cloth). The sellag or thread for the background color of the woof is wound on a stick called anak tulak that can turn into a bamboo shuttle called tulak. A proficient weaver would require a lesser number of threads in the tulak, which they would refer as “sellag mintedde” or a single weft thread, resulting to an embossed and tight cloth. Thicker threads that make up the pattern called “sulip” (supplementary weft) are placed in between the warp threads as the pattern requires.

The word “tennun” in Yakan generally means “woven cloth.” These cloths are used in making the Yakan dress. Often, Yakan textiles are mistakenly described as ‘embroidered’ by people not familiar with the production process. In addition, there are different categories of a Yakan cloth. All these have been mastered by Ambalang. Her artistry and craftsmanship is best expressed in the bunga sama, sinelu’an, and seputangan categories.

First, the Bunga-sama, also, “fruit of the ancestors,” referring to rice, is a design or category of cloth or weaving with the rice grain-like motif, with elaborate and bolder designs. It is utilized as blouse and pants material and restricted only to a high status Yakan, specially the suwah bekkat (cross-stitch-like embellishment) and suwah pendan (embroidery-like embellishment) pieces. Motifs in the bunga-sama are inspired by the plants and animals in their surroundings, and more importantly, of the Yakan’s great respect for the “paley (rice),” as diamonds and grain-like motifs are often seen on the span of the warp. A master weaver like Apuh Ambalang can execute the bunga-sama teed peneh pitumpuh (the cloth with seventy-designs; at times with seven different colors of thread), the peneh sawe-sawe (snake skin-like), peneh dawen-dawen (leaf-like), peneh palipattang which is archaic for peneh beras-beras (rows of unhusked grains or grain-like), peneh kenna-kenna (fish-like), peneh manuk-manuk (bird-like), peneh kaka-kaka (crab-like), and the peneh ampat kaban-buddi (four diamonds within a frame; patchwork-like). (Pasilan, 2016b)

Another exemplary work of Apuh is the sinelu’an teed which is regarded as the most intricate of all Yakan textiles. This is a cloth or design utilized for blouse (for men only) and trouser material. This a type of weaving with vertical stripes. Each of the stripes has an elaborate pattern of miniscule diamonds and incised triangles resembling the sections of the bamboo, coming from a belief, that the “paley” should grow tall and strong like the bamboo. This bamboo-like patterned cloth has tiny bands of zigzags called kalis-kalis (incisions), miniscule diamonds called bulak-bulak (grain-like), minute horizontal lines called “babag” or commonly referred nowadays as “birey-birey,” that separate the motifs into tiny segments resembling the sections of the bamboo called batak or honga. Also, there are small bands of diamonds inside the bulak-bulak called lepoq-lepoq, and in its center, the apuh-apuh, a dot-like motif. There are also vertical rows of small dashes called olet-olet, sipit-sipit, or lelipan-lelipan (caterpillarlike), rows of crab like motifs called kaka-kaka, a panel of jarlike motif called komboh-komboh, and plain vertical lines or columns called bettik (resembling the contour of the land when planting in straight lines). (Pasilan, 2016b)

The seputangan teed, which required any weaver’s utmost precision, as it does not have a tangible guide nor it is pre-patterned, (which not all Yakan weavers could do) is the most intricate in a Yakan female ensemble. It is a meter square in size with geometric designs and is the most expensive article of Yakan clothing due to its intricacy. . The pussuk labung (saw tooth design), harren owak (crow steps gable-like) sipit-sipit or subid-subid (twilled like), dawen-dawen (leaf like), harren-harren (staircases), kaban-buddi (diamonds/ triangles), dinglu-dinglu or mata-mata (diamond/ eye), and buwani-buwani (honeycomb-like) designs are evident in this type of cloth. The term balikat-balikat refers to the sides of the “seputangan” woven with small triangulate or diamond patterns. The pinggil-pinggil refers to the in-woven triangles and diamonds of a balikat-balikat section of the seputangan. The seputangan is a symbolic representation of the Yakan’s pangubatan (altar set at the center of the field before the actual planting) and its diamonds, symbolized the palay. This piece of cloth is folded and tied over the olos to tighten the hold of the skirt on the waist. It may also be worn as a head covering. It is also placed on the shoulders of brides and grooms during weddings.

To Ambalang’s belief, which she took from her ancestors, diamonds represent rice grains and symbolize wealth. When four stars form together like a single diamond at the sky meant that harvest is approaching and will be plentiful. The diamonds are called “mata-mata” or “dinglu-dinglu”. The depiction of mountains, “punoh-punoh” (mountain like), is set at the sides of the bunga-sama called “higad-higad” or “sing” or the “balikat-balikat” of the saputangan”. The Xs represent rice mortars which are arranged in clusters along with the diamonds to form an interesting illusion. The interplay of Xs and diamonds symbolizes wealth and abundance in harvest. This particular pattern is seen on a seputangan, a Yakan headcloth, and inalaman, a high status over-skirt. A floral motif is considered to be one of the most popular sources seen on bunga-sama or border of an inalaman. The fairy or butterfly wings, locally known as the “kaba-kaba” or wing-like motif, as seen in the “bunga-sama teed peneh pitumpuh”, is the most intricate in the “bunga-sama” category. The snake is considered as a vehicle of the spirits as in the “mailikidjabaniya.” This particular pattern, seen on the “bunga-sama”, is used for making pants which symbolizes power and authority and was mainly reserved only for male members of royalty or rich clans. (Pasilan, 2016a)

In Yakan weaving, most of the animal and plant motifs are realistically represented in their textiles. They have deemed nature as the mother of art and they wanted to record their pure naturalistic beauty. The designs reflect the Yakan’s nature of habitation or occupation as agriculturists as each cloth patterning is symbolic of the “palay,” which also depicted power, social status and self-expression. The minuteness and compressed detail of a motif or design symbolizes the Yakan’s sense of “community”, “togetherness” or “harmony”.

Through her recollection of the earliest strategies and techniques learned from her mother, Ambalang started training Vilma, her daughter, and some of her nieces, of whom she sees good future for the continuity of her craft and a culture passed on through generations of gifted weavers. For Ambalang to create such artistry, she has to be in harmony with her soul, her spirit ancestors, her environment, her tools, her threads, her loom, and her Creator. The Yakan weaving engages the weaver’s body and soul, and all the elements that surround her.

The tennun Yakan is an important embodiment of Yakan culture. Its categories, colors, designs or motifs and significance will continually remind Ambalang, and her works of what it means to be a Yakan – people of the earth— who may have lived in an island that have been through human created conflicts, yet through her craft, Ambalang reaffirms their Yakan identity as a people who continuously weaves the threads of culture from the past to the present and become cultural treasures for the new generation Yakan, the Filipinos and all of humanity in the future. (Pasilan, 2016a)

Author: Pasilan, Earl Francis C.

Photos: National Museum Western-Southern Mindanao

References: Pasilan, Earl Francis C. (2016a) “Ambalang Ausalin: A’a Pandey Megtetennun” in 2016 National Living Treasures/ GAMABA Folio. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts. ——- (2016b) “Pansak Yakan: Dances of the Yakan from Lamitan, Basilan” (Master’s Thesis, Southwestern University PHINMA, Cebu City).

As we draw to a close the celebration of #NationalWomenMonth2022, we are sharing the highlights of the #NationalMuseumPH lecture

As we draw to a close the celebration of #NationalWomenMonth2022, we are sharing the highlights of the #NationalMuseumPH lecture

An open forum was very lively and interactive and there was not enough time to entertain the questions from the attentive participants. Bobby Orillaneda, Senior Museum Researcher and Officer-in-Charge of the Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division provided an in-depth recap of the wonderful talks, which he described as enriching and an eye-opener. He hoped that the participants learned from the webinar and that this knowledge equips them when confronted with gender issues in the field. He expressed support for women’s endeavors and agreed that archaeology is for everyone interested, regardless of gender.

An open forum was very lively and interactive and there was not enough time to entertain the questions from the attentive participants. Bobby Orillaneda, Senior Museum Researcher and Officer-in-Charge of the Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division provided an in-depth recap of the wonderful talks, which he described as enriching and an eye-opener. He hoped that the participants learned from the webinar and that this knowledge equips them when confronted with gender issues in the field. He expressed support for women’s endeavors and agreed that archaeology is for everyone interested, regardless of gender.