Undas 2021 (Atang)

Undas 2021 (Atang)

-

November 2 – Undas (Atang) B

-

November 2 – Undas (Atang) A

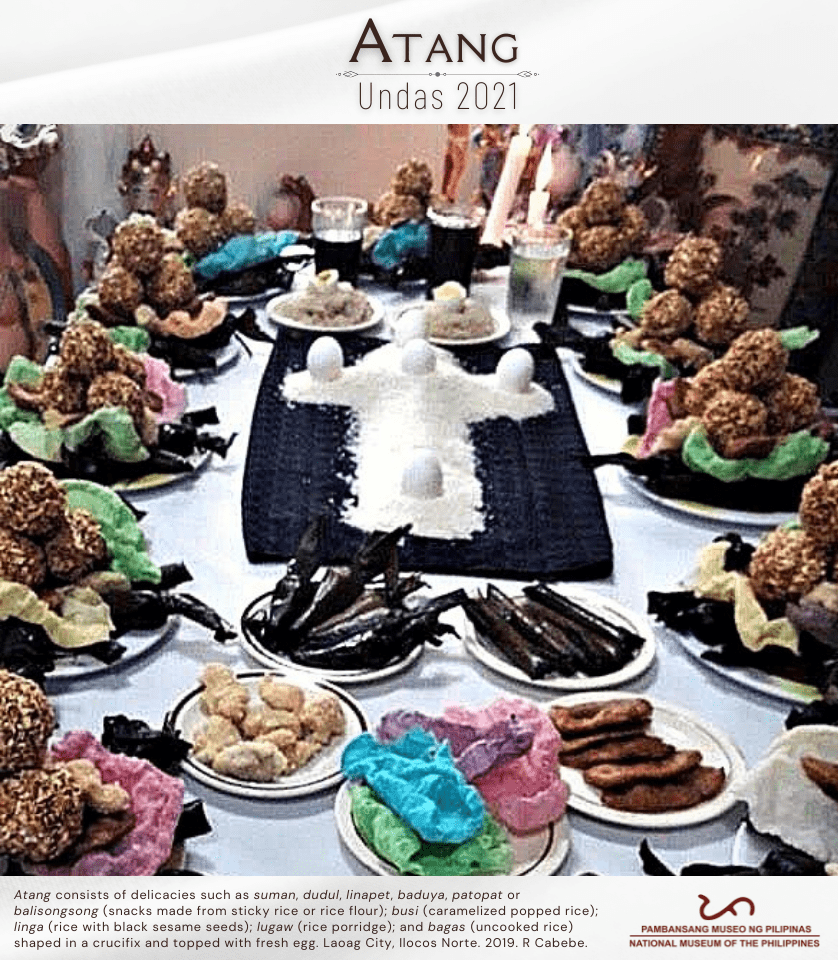

In the continuing observance of #Undas2021 with our Filipino brothers and sisters today, All Souls’ Day, our #MuseumFromHome series features the tradition of atang, or offering of food for the dead, practiced by the Ilocanos in the Ilocos region.

Atang is usually done during Undas and on other occasions. This act of offering food for the dead is also practiced as alay among Tagalogs, and halad among Cebuanos.

Plates of food prepared for an atang consist of delicacies such as suman, dudul, linapet, baduya, patopat or balisongsong (snacks made from sticky rice or rice flour); busi (caramelized popped rice); linga (black sesame seeds); sticky rice with coconut milk; and bagas (uncooked rice) shaped in a crucifix and topped with fresh eggs. The food may also be accompanied by bua ken gawed (betel nut and piper leaf), apog (lime powder), basi (fermented sugarcane wine), and tabako (tobacco). These offerings are placed in front of a photo of the departed and/or image of Jesus, Mary, or the Holy Family during wakes and anniversaries in homes or in front of the graves, after which the family and/or mourners of the deceased may also offer prayers.

Ilocanos believe that the soul has not yet left the world of the living during the wake and still needs sustenance, hence the offering of food as they transcend onto the afterlife. It is also believed that the soul returns to the land of the living after the 9-day wake and must be welcomed back. In instances when the deceased appears in a dream or when a family member suddenly experiences unexplainable sickness, atang is performed as an appeasement ritual for the deceased who may have been offended or disturbed. It is also interpreted as asking the deceased to intercede for their loved ones, and thanking them for warning against bad omen through dreams. Clearly, the significance of the atang for the Ilocanos goes beyond the remembrance and honoring of the dead loved ones. It connotes their view of life after death and the relation of the living to the departed.

While visiting graves during Undas are not allowed this year due to precautions against COVID-19, traditions such as atang, remind us of how much Filipinos value their relationship with their loved ones, which is still carefully maintained even as they transcended to the afterlife.

#Atang

#Undas2021

#AllSaintsDay

#AllSoulsDay

Text by the NMP Ethnology Division and photos from MLI Ingel and MP Tauro

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)