Santa Cruz shipwreck Incense Burners

Santa Cruz shipwreck Incense Burners

-

Santa Cruz Incense Burner_Poster 1

-

Myanmar celadon dishes

-

Santa Cruz Junk

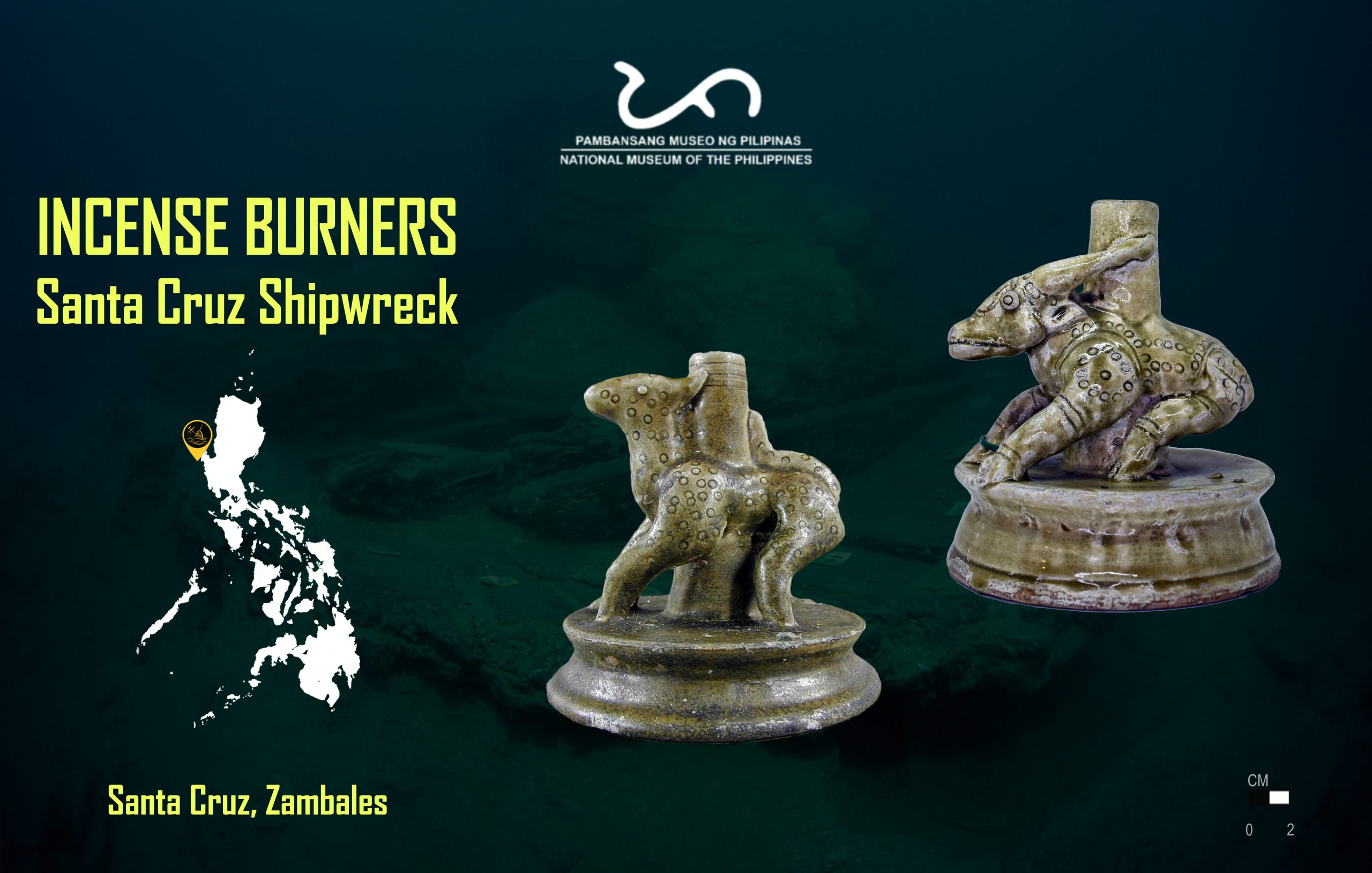

This week on #MaritimeMonday highlights two incense burners from the Santa Cruz shipwreck. The vessel carried predominantly Chinese stoneware and porcelain ceramics, and limited amounts of Thai, Vietnamese and Burmese/Myanmar stoneware. The non-ceramic items include iron, glass, wood, and stone objects, as well as organic remains. For more information about the Santa Cruz shipwreck, please see https://tinyurl.com/SantaCruzShipwreck.

Among the recovered materials were two remarkable stoneware animal figurines in the form of a deer and an ox, used as incense burners. These are high-fired, green-glazed stoneware pieces with stamped circular incisions on their bodies and supported by circular pedestals. Their tubes for the incense or possibly candle sticks are mounted at the back of the animals. They were initially identified to have been produced by the Si Satchanalai kilns in Thailand, but recent excavations in the kilns in present-day Twante Township, Yangon region in Myanmar proved otherwise. The incense burners, along with the celadon dishes also produced by the Twante kilns that were also part of the Santa Cruz cargo, are significant. These give direct material evidence of Myanmar’s engagement with foreign trade during the 15th and early 16th centuries Common Era that was not evident in extant historical records.

The #NationalMuseumPH is now open to the public but visits are by appointment through this website. Monitor our social media pages such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for further announcements. In the meantime, you may watch the virtual tour of the upgraded ‘300 Years of Maritime Trade in the Philippines’ exhibition here: https://tinyurl.com/300YearsOfMaritimeTradePH

#IncenseBurner

Poster and text by the Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division

Photos © Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio/Far Eastern Foundation for Nautical Archaeology

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)

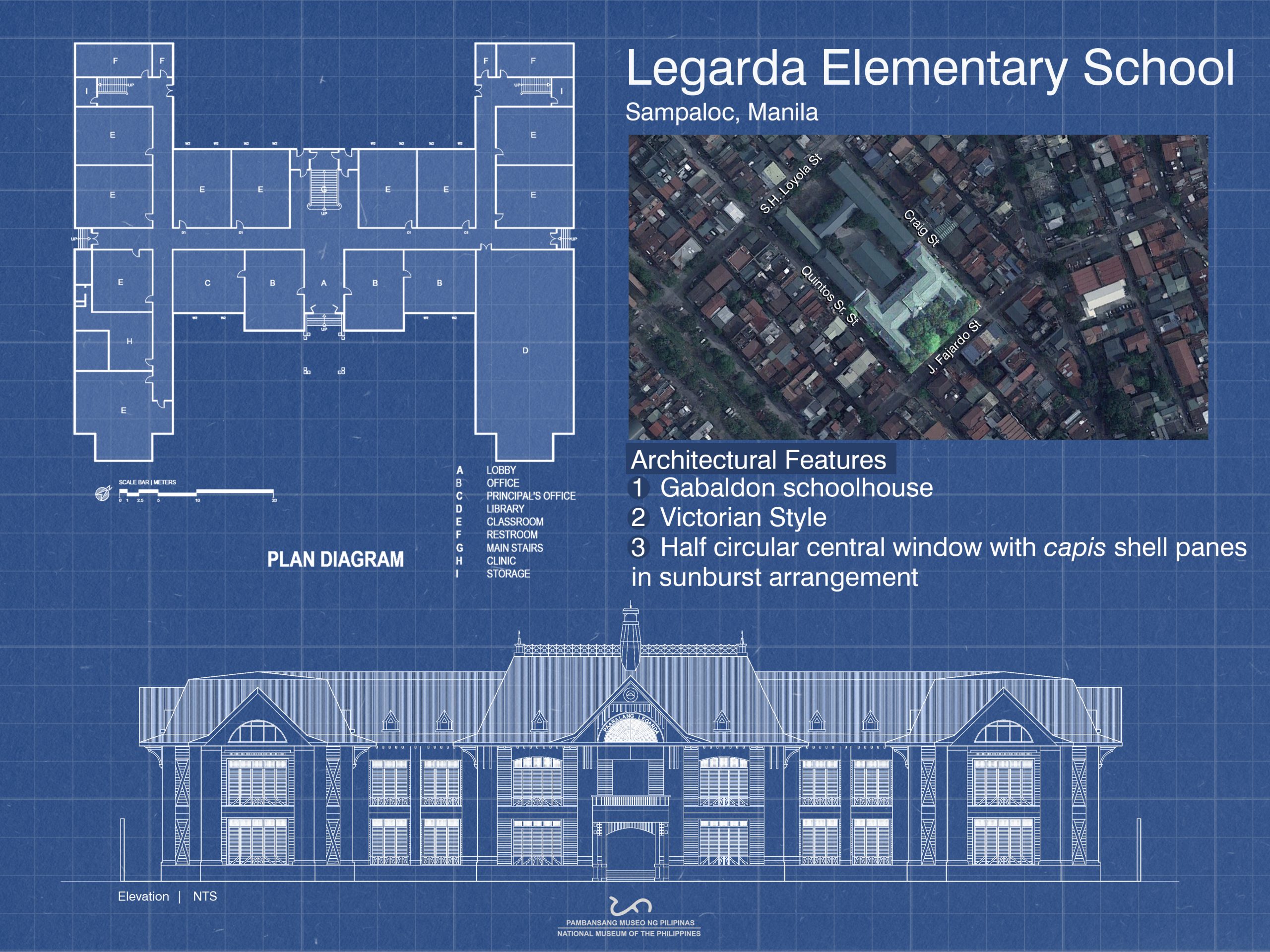

Paaralang Legarda

Paaralang Legarda  Established in 1922,

Established in 1922,  One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of

One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of  The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the

The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the