Legarda Elementary School

Legarda Elementary School

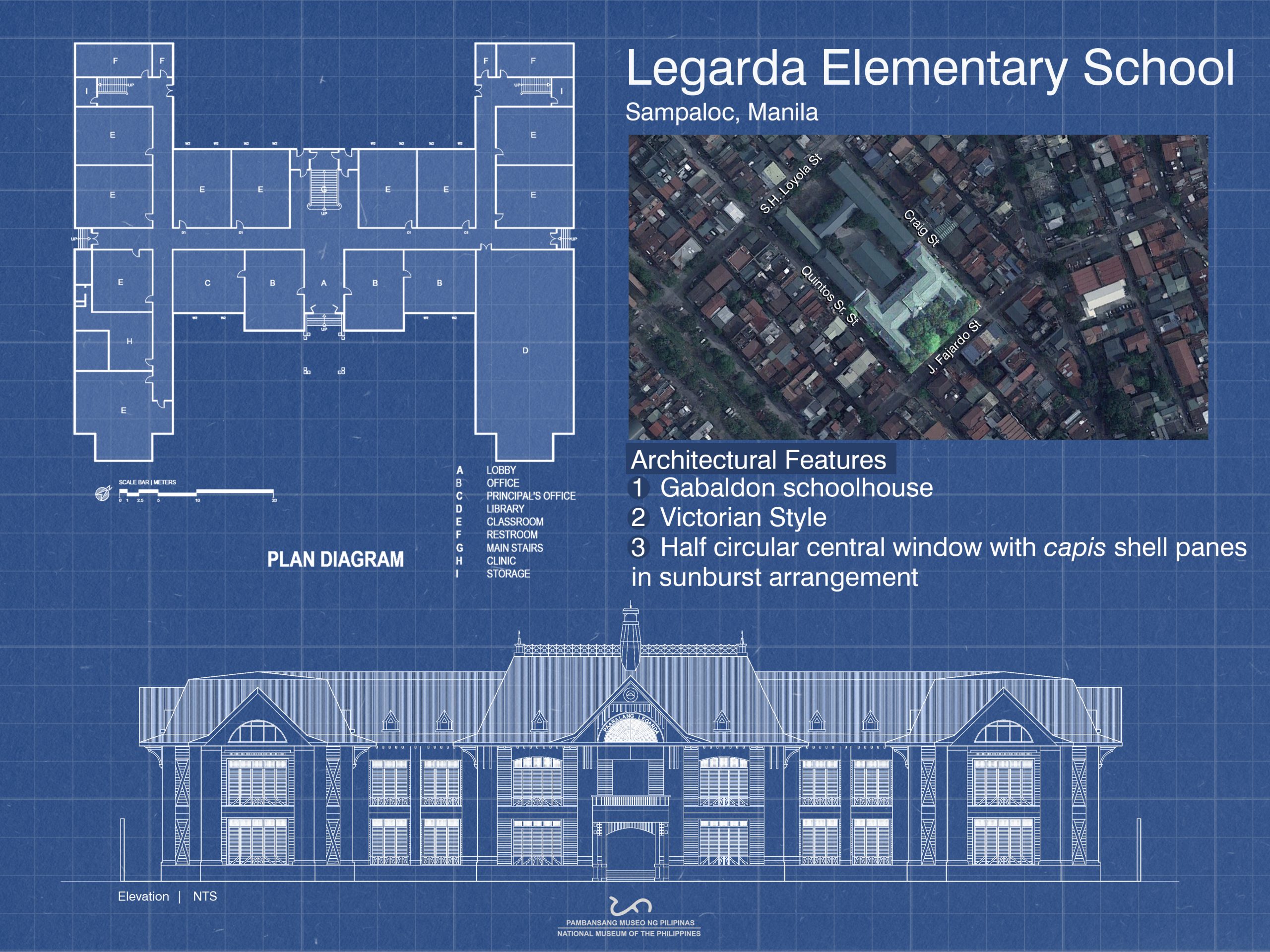

For today’s #BuiltTraditionThursday series, we feature one of the structures displayed at the Placuna placenta (capis) exhibition, the Legarda Elementary School. Located in Sampaloc, Manila amidst the residential zone of the district, Paaralang Legarda or Legarda Elementary School stands on a large block bounded by Jacobo Fajardo, Craig, Sergio H. Loyola, and Eduardo Quintos Streets.

Paaralang Legarda is one of the Gabaldon Schoolhouses in Manila. During the American period, education was a prime concern hence school building construction was a priority in infrastructure development. Gabaldon Act (Act. No. 1801) was introduced by Congressman Isauro Gabaldon of Nueva Ecija and was enacted by the Philippine Legislature on the 20th of December in 1907. With William E. Parsons as the architect, the standardized design considers the tropical climate, earthquakes, insect infestation, local building materials, styles, and motifs. The curriculum also largely shaped the planning of the school buildings, which considers learning and teaching spaces especially for home economics and livelihood programs.

Paaralang Legarda is one of the Gabaldon Schoolhouses in Manila. During the American period, education was a prime concern hence school building construction was a priority in infrastructure development. Gabaldon Act (Act. No. 1801) was introduced by Congressman Isauro Gabaldon of Nueva Ecija and was enacted by the Philippine Legislature on the 20th of December in 1907. With William E. Parsons as the architect, the standardized design considers the tropical climate, earthquakes, insect infestation, local building materials, styles, and motifs. The curriculum also largely shaped the planning of the school buildings, which considers learning and teaching spaces especially for home economics and livelihood programs.

Established in 1922, Paaralang Legarda displays a Victorian style of architecture. From the southeast side along J. Fajardo Street, the entrance opens to a driveway and garden with lush and rich foliage. Coming to view is the wooden main building designed by Andres Luna de San Pedro. The main building, with an over-all 60.60-meter length and 49.95-meter width, is H-shaped in plan. The portico’s deck is skirted by low stone balusters and leads the eye to the central part of the building as it is topped off by a main gable with wooden bracket articulation. The mansard roof, with projecting small gables and dormers, are architectural elements indicating American influence. Portions of the mansard roof behind the main gable have wrought iron grilles on edges with a turret at its center. Exterior walls are made of wood with weathercut sidings. Another distinctive feature is regularly occurring eaves brackets in simple straight and curving embellishment.

Established in 1922, Paaralang Legarda displays a Victorian style of architecture. From the southeast side along J. Fajardo Street, the entrance opens to a driveway and garden with lush and rich foliage. Coming to view is the wooden main building designed by Andres Luna de San Pedro. The main building, with an over-all 60.60-meter length and 49.95-meter width, is H-shaped in plan. The portico’s deck is skirted by low stone balusters and leads the eye to the central part of the building as it is topped off by a main gable with wooden bracket articulation. The mansard roof, with projecting small gables and dormers, are architectural elements indicating American influence. Portions of the mansard roof behind the main gable have wrought iron grilles on edges with a turret at its center. Exterior walls are made of wood with weathercut sidings. Another distinctive feature is regularly occurring eaves brackets in simple straight and curving embellishment.

One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of Paaralang Legarda. Now, it was replaced by modern sets of glass jalousies while the capis shell panels on its transoms are retained. On the main gable at the main building’s central axis emphasizes a half circular window in sunburst pattern which originally has capis shell panes.

One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of Paaralang Legarda. Now, it was replaced by modern sets of glass jalousies while the capis shell panels on its transoms are retained. On the main gable at the main building’s central axis emphasizes a half circular window in sunburst pattern which originally has capis shell panes.

The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the Placuna placenta exhibition at Gallery 20 of the National Museum of Fine Arts to see and learn more about the use of capis shell windows in Manila’s built heritage.

The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the Placuna placenta exhibition at Gallery 20 of the National Museum of Fine Arts to see and learn more about the use of capis shell windows in Manila’s built heritage.

Text and illustrations by Ar. Bernadette B. Balaguer and photos by Erick E. Estonanto and Ar. Armando Arciaga III | NMP AABHD