Ancient Burial Spaces and Places

Ancient Burial Spaces and Places

-

1

-

2

-

3

Continuing with the #TrowelTuesday’s November theme on mortuary topics in the context of Philippine archaeology, we are featuring the ancient burial spaces and places to better understand past cultures.

Spaces and places for the dead in the Philippines during ancient times were found in varied environments and locales such as caves, open sites, and coastal or inland locations.

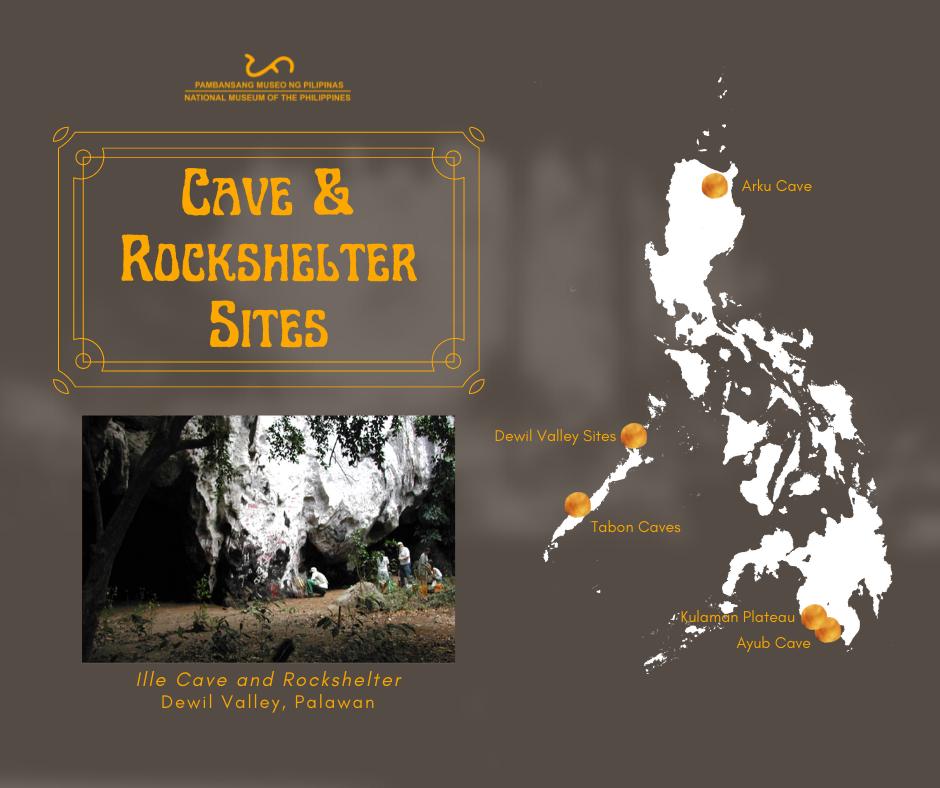

The earliest evidence for deliberate burials in the Philippines is thus far found within the cave and rockshelter locale of Ille Cave in El Nido, Palawan, where evidence of cremation burials dated 9000 years ago were found. Caves in karst landscapes are conventional spaces for the dead throughout the Philippine Neolithic (4200 to 2500 years ago) and Metal Age (2500–1500 years ago), as demonstrated by several sites in Duyong Cave and the Dewil Valley in Palawan; Arku Cave in Peñablanca, Cagayan; Ayub Cave in Maitum, Sarangani; and the Kulaman Plateau in Sultan Kudarat (formerly South Cotabato).

While funerary sites in caves are common, some cultures preferred to bury their dead in open areas especially in the later Metal, Protohistoric, and Historic periods. These open cemeteries were found along coasts, riverbanks, or inland areas. For instance, coastal areas were chosen locales for the 2500-year-old jar burials and 300- to 400-year-old boat-shaped stone cairns in Batanes (read more: https://tinyurl.com/BatanesBoatShapedBurials); the 14th–16th-century inhumations in Calatagan, Batangas; and the late 16th–early 17th-century burials of Boljoon, Cebu (read here: https://tinyurl.com/BoljoonEarlyHistoricBurials).

Meanwhile, locales along riverbanks of Santa Ana, Manila in the 12th to 14th century, and inland spaces for the 15th-century jar burials in Cabarruan, Solana, Cagayan were preferred cemetery spaces by other cultural groups.

As human responses to death are often dictated by society, the choice of burial spaces can reveal cosmologies of past cultures. Patterns found in archaeological data such as landscapes and iconography in artifacts suggest a linkage between people, spaces, and ancient cosmologies through time. Decorative motifs in ceramic artifacts, specifically in images such as sun, bird, and reptile, suggest that past cultures in the Philippines subscribed to a pan-regional cosmology of a tripartite universe that was prevalent across Southeast Asia in antiquity.

Your #NationalMuseumPH has been re-opened to the public. Book a slot or explore our galleries through a virtual tour through this website.

#AncientPlacesOfDeath

#ArchaeologyOfTheDead

#MuseumFromHome

#VictoryAndHumanity

#YearOfFilipinoPrecolonialAncestors

Text by Alexandra de Leon and posters by Timothy James Vitales | NMP Archaeology Division

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)