Birth Anniversary of Agnes Arellano

On the 72nd birthday of sculptor Agnes Arellano, the #NationalMuseumPh features this sculpture by the artist born #OnThisDay in 1949.

Born in San Juan, Rizal, in 1949, Agnes Arellano belonged to a prominent family of architects. She studied psychology at the University of the Philippines. After she graduated in 1971, she took up further studies and enrolled in a master’s degree in Clinical Psychology at the Ateneo de Manila. During the Martial Law, the government imposed a strict travel ban. The government allowed pilgrimages to the sacred sites in Europe during the Holy Roman Catholic Year. During her travels to Europe, she was exposed to western art. She was inspired by the works of master artists like Michelangelo and Van Gogh. Upon her return to the Philippines, she studied Fine Arts majoring in sculpture in 1979 under National Artist Napoleon Abueva, a pioneering modernist in sculpture. She was also greatly influenced by conceptual artist Roberto Chabet. Since her artistic career started, Arellano has exhibited here and abroad in Berlin, Fukuoka, Havana, Johannesburg, New York, Brisbane, and Singapore.

Arellano is best known for making surrealist and life-size expressionist sculptures primarily in plaster. Her works focus on feminist issues and show how women are traditionally portrayed by reinterpreting local myths.

The National Museum takes pride in Arellano’s work, “Eshu,” which is currently on exhibition at the Philippine Modern Sculptures Hall (Gallery XXIX) of the National Museum of Fine Arts. Eshu, in African traditions, most especially with the Nigerian belief, is the Lord of the Crossroads or God of Fate. This volcanic cinder and cold-cast marble is a fantasy self-portrait cast and directly modeled by the artist.

The Philippine Modern Sculptures Hall is temporarily closed to give way to an upgraded exhibition. Watch out for updates on this page and follow our official Twitter and Instagram accounts.

We are open! Reserve your slot and visit the other galleries at the National Museum of Fine Arts (NMFA). View the 360 Virtual Tour of the nine select galleries at the NMFA through this website.

#OnThisDay

#AgnesArellano

#MuseumFromHome

Text and photo by NMP FAD

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)

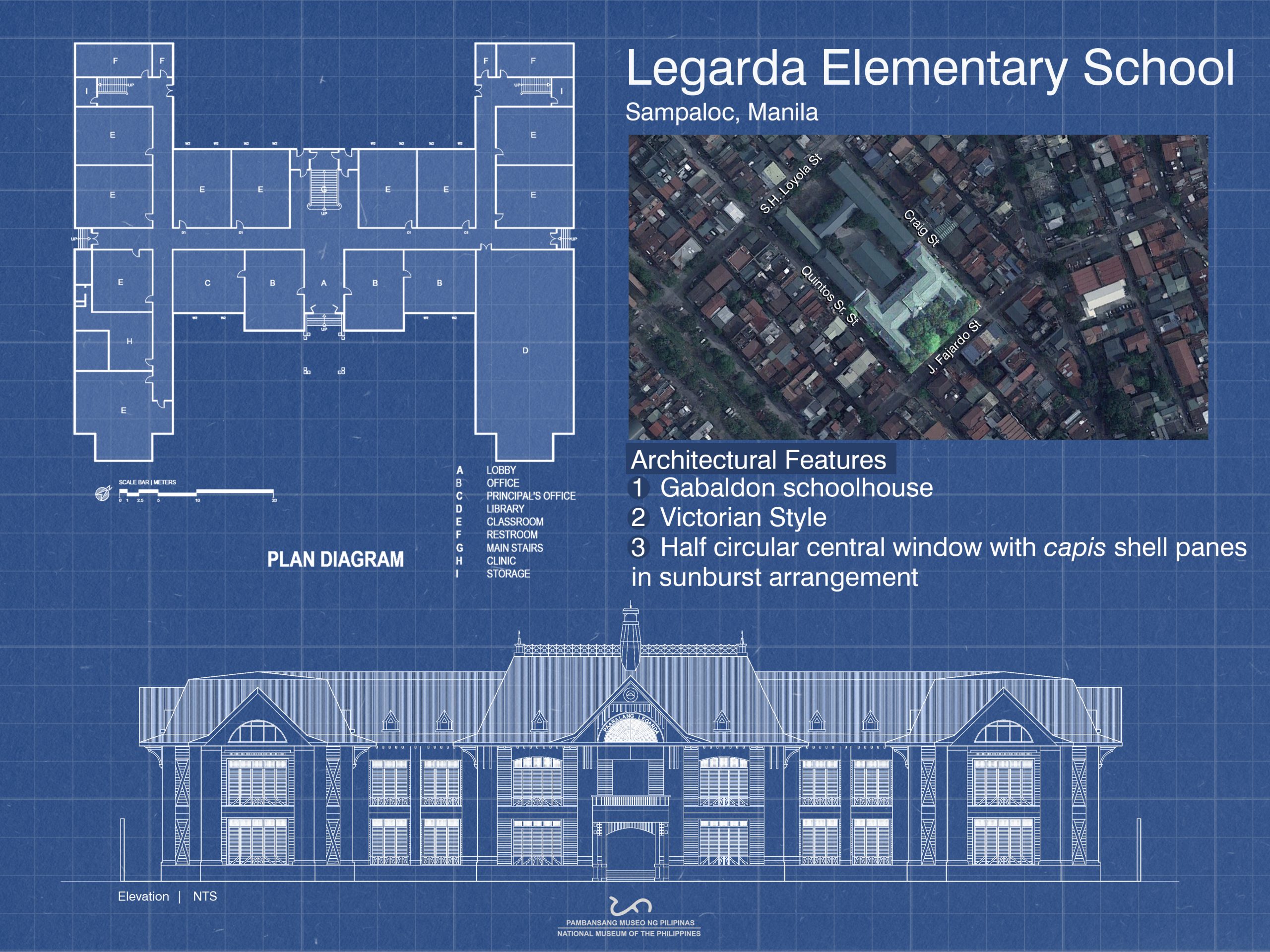

Paaralang Legarda

Paaralang Legarda  Established in 1922,

Established in 1922,  One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of

One feature of Gabaldon schoolhouse are awning-type windows with capis shell panes originally seen on the main building of  The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the

The Legarda Elementary School exemplifies not only a venue of learning and development, but also a historical structure with aesthetic value worthy of preservation and appreciation. Drop by the